Arnold Mendelssohn

the RebellFather: Nathan

Mother: Henriette

Siblings: Wilhelm, Ottilie

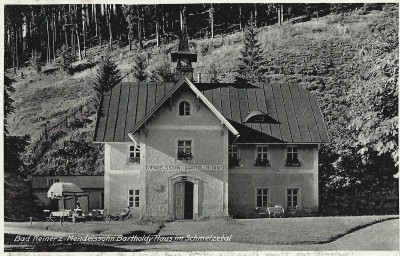

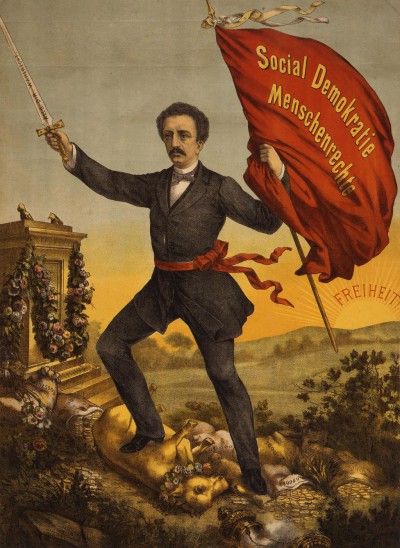

His father Nathan – the youngest son of Moses Mendelssohn and a mechanically gifted tinkerer and toolmaker – had embarked upon a number of ambitious but ill-fated entrepreneurial projects, such as a foundry in Reinerz. He eventually had no choice but to work as a government bureaucrat to provide for his family. Arnold, who exhibits talents in many areas, tries to escape his strict and confining home environment. He studies medicine in Bonn and Berlin and works in the Berlin laboratory of the famous physiologist Johannes Müller, showing great promise for his medical dissertation. After becoming a doctor, he cares for the poor of the “Voigtland Slum” near Rosenthaler Tor in Berlin. Concomitantly, he also embarks upon a formal study of philosophy along with his university friend Ferdinand Lassalle, an acquaintance from Silesia.

In order to live in style on a par with his student roommates Ferdinand Lassalle and Alexander Oppenheim, who come from wealthy backgrounds, Arnold cadges money from his banker uncle Joseph Mendelssohn. He tries to convince various relatives to redirect their charitable contributions for poverty relief towards the setup of a credit union for the indigent. They react with skepticism, particularly in light of Arnold’s unquestioning loyalty to the charismatic Lassalle. His social prospects are permanently ruined in 1846, when he and Alexander Oppenheim perpetrate a ham-handed theft of documents in an Aachen hotel for the benefit of a female legal client of Lassalle’s (the so-called “Cassette Affair”). Sought by the police, Arnold flees to Paris, where he seeks help from Heinrich Heine and makes the acquaintance of the Zionist pioneer Moses Hess. Inspired by Anarchist theories, Arnold continues to daydream about his plans for a “people’s bank.” After Oppenheim and Lassalle, the sons of millionaires, are legally exonerated in the Cassette Affair, Arnold confidently turns himself in to the Prussian authorities. To his dismay, he is sentenced to incarceration just as the 1848 revolution is about to break out in Prussia. His 14-page letter to his father ends on a desperate note: “You yourself were one of the first who called me a ‘Communist’ (as a curse word) and you threatened that you would face down our ideas with cannons. In other, similar contexts it was your wont to say, ‘He’s determined to have his rights, he’s looking to get shot dead.’ Well I’ve now been shot dead. So then, please be so kind as to let me out of the hole now: let no one feel sorry for having made it happen or for having helped it along.” (April 22nd, 1849).

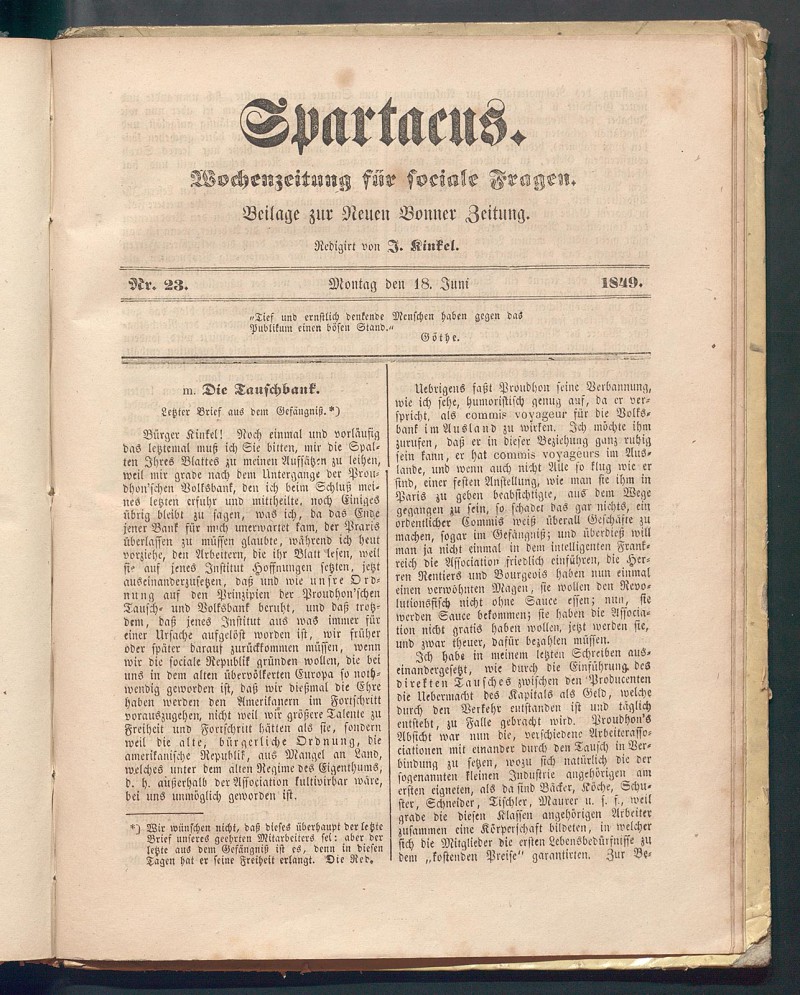

While in prison, Arnold used the newspaper Spartacus to publish anonymous manifestos about his ideas for a “barter bank” and for a more equitable economic system. Appeals for clemency by his family and by Alexander von Humboldt are initially rejected; a public petition is even launched on his behalf. His remaining sentence is eventually commuted, but under the condition that he leave Europe for good.

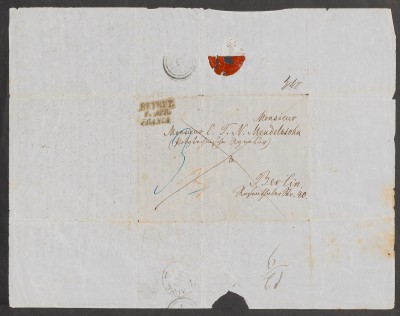

During his final years, Arnold Mendelssohn crisscrosses Southern Europe and the Near East as a refugee, physician, and war correspondent. Due to his contacts with Hungarian revolutionaries, he is once again hauled into court, this time by the Hapsburg authorities. He pursues an official appointment as a physician in the Ottoman Empire, but is thwarted by the intervention of Prussian and Austrian diplomats. After eking out a living as a village doctor, he is instrumental in helping to found the “Hospital St. Louis” in Jerusalem. This still stands and today serves as a hospice for Muslims, Jews, and Christians.

In order to win the Latin Patriarch’s support for his hospital project, Arnold converts from Protestantism to the Catholic Church. He sends a slew of Levantine Letters to European newspapers from Jerusalem, Lebanon, Syria, and the Crimean war theater, while also corresponding with a mysterious “Madame” living in Europe. The London and Cologne papers print his reports of intercultural experiences made while travelling in Arab garb. Arnold portrays Ottoman religious toleration as more progressive than the European approach. The outbreak of the Crimean War puts an end to Arnold’s hopes of emigrating to America and reuniting there with this brother Wilhelm. He becomes a medic for the army of the Ottoman Sultan, where many other European revolutionaries are also serving in Turkish uniform. In 1854, Arnold Mendelssohn succumbs to typhus during a campaign near the Turkish-Armenian border.