Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy

The EnlightenerFather: Carl Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Mother: Mathilde von Merkl

Siblings: Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Der literarisch und musikalisch vielseitig begabte Enkel des Komponisten Mendelssohn Bartholdy wächst unter starken Frauen auf. Sein Leipziger Jura-Professor, Doktorvater und Mentor Adolph Wach, der mit einer Tante Albrechts, der Felix-Tochter Marie, verheiratet ist, wird zugleich sein Ersatz- und Schwiegervater.

The grandson of the composer Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, gifted with many and varied literary and musical talents, grows up in the company of strong women. His Leipzig law professor, doctoral advisor, and mentor Adolph Wach, who is married to Albrecht’s aunt Marie, daughter of Felix, also becomes his father-in-law and substitute father figure.

As a law student, Albrecht publishes Schmetterlinge (Butterflies), a collection of poems, his previous lyric poetry having already won the Fichte Prize. He also writes librettos, composes lieder, and, as a professor in Würzburg, establishes the Jenaer Festspiele, an annual music festival held in honor of the composer Max Reger. During World War I, Albrecht joins a pacifist initiative comprised of many prominent academics. In 1917, the year before the Armistice, he holds a series of lectures on “Civic Virtues during Wartime and Peace” in which he describes the notion of “constancy”. The essential thing, he argues is “to impart to those who come into the city after us the true treasures of the community; but not as a dead commodity, as an inheritance of a hundred or a thousand million that they merely have to pay taxes on and squirrel away in the tried-and-tested bank and then forget about; no, it must be passed down to them in a way that makes them understand that what is coming their way is a part of themselves. … My ancestors include a long line of Jewish rabbis going back to the Middle Ages, and among them is also an equally long line of pastors and provosts and martyrs for the faith from the French Huguenot community going back to the times of the Edict of Nantes; they also include German Lutheran pastors from the Reformation period and a fourth avuncular line of upright Catholic Austrians. This is probably true for many of us. And still I aver that, even for those of us with such a patchwork heritage, it is the faith of our forefathers which must lay the foundations for living in our soul, if we are to become good citizens of this world and of our homeland.”

At the post-war peace negotiations in Versailles, Professor Mendelssohn Bartholdy is one of the academics in the German delegation’s accompanying team of experts. An excellent pianist, he supposedly provides acoustic cover for the negotiations with his playing, since the Germans fear being eavesdropped upon.

Commissioned shortly after the war by the Weimar government to edit the diplomatic files pertaining to Germany’s pre-1914 foreign policy, the legal scholar with the prominent name concludes to his chagrin that he cannot in good conscience comply with his superiors’ wish to build a case rebutting Germany’s guilt in starting the war. He goes on to publish the journal Europäische Gespräche (European Conversations) and, with financial assistance from the Warburg family, founds the Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik (Hamburg Institute for Foreign Policy). The aim of both endeavors is to help strengthen the bonds that tie the fledgling German democracy to the family of nations and to a shared system of international law. Some of the people working for him at the institute will later risk their lives in the resistance against the “Third Reich.” As Professor of International Law at the newly inaugurated University of Hamburg, Albrecht encourages the Germans to tie in their political fortunes with the Western democracies. Thus, he establishes the American Library in Hamburg, a US-German Friendship Association and the magazine Hamburg-Amerika-Post. He represents Germany at the League of Nations and before the affiliated Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague.

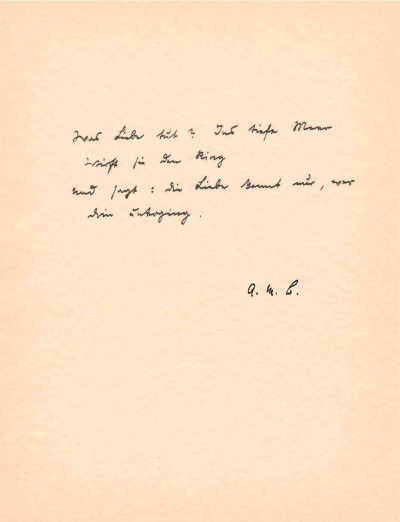

The creativity of the amateur composer Albrecht is also nurtured by his intense relationships with various women who serve as unattainable muses. One is his sister-in-law Marie “Mirzl” Wach (1877 – 1964), with whom he remains on close terms before and after his marriage and to whom he dedicates passionate love songs. Another such muse in the sunset years of his life – and the subject of equally devoted songs – is his long-time assistant Magdalena Schoch, the first woman to publish a Habilitationsschrift in law in Germany. A few years ago, a set of 70 lieder by her former boss was found in Schoch’s estate near Washington D.C.

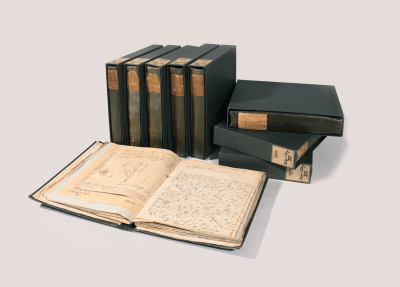

In 1905, Albrecht marries his cousin Dora Wach (1875 –1949), with whom he later adopts two girls orphaned by WWI. Once the Nazis come to power in Germany, Mendelssohn Bartholdy is forced out of his professorship and expelled from his faculty due to his “non-Aryan” ethnic origins. In 1934, he decides to risk a perilous escape to England via Switzerland, and is eventually followed by his family. This escape route allows him to also rescue the so-called “Green Books,” the 27-volume collection of letters written by his grandfather Felix. In Oxford, where he obtains a teaching position, the emigré chafes under the English appeasement policy towards Hitler, hoping in vain that a tyrannicide would intervene to free Germany from despotism. He dies of stomach cancer not long after; his political testament, “The War and German Society,” is published posthumously. Although barely legible, the gravestone of this pioneering German pacifist thinker can be found in the village churchyard of Clifton Hampden, high above the Thames River. In 2012, a post-graduate law school and student dormitory in Hamburg are named after him.